Introduction

Most marketing and pricing textbooks will outline the cost-plus pricing method and its formula. It is a helpful approach for understanding the input and production costs of running the business and ensures that retail price points are set at least (preferably more) at a level where costs are covered.

There are multiple articles on cost-plus pricing on The Marketing Study Guide website, please refer to the links at the bottom of this post for further information.

Contents

- The Key Limitations of Cost-Plus Pricing

- It Does Not Consider Competitive Pricing

- It Does Not Consider Customer Value

- We Could Leave Money on the Table by Under-Pricing

- We May Become Careless with Cost Control

- Prices Will Become Too Dynamic

- The Price Point Does Not Consider Profit Maximization

- There is No Consideration of Our Positioning

- It Ignores Our Goals and Strategy

- The Challenge of Identify and Allocating Costs per Product Line

The Key Limitations of Cost-Plus Pricing

Although cost-plus pricing is a relatively simple to setting retail prices, it is a pricing approach that needs to be used with care. This is because there are multiple limitations and challenges with this pricing method.

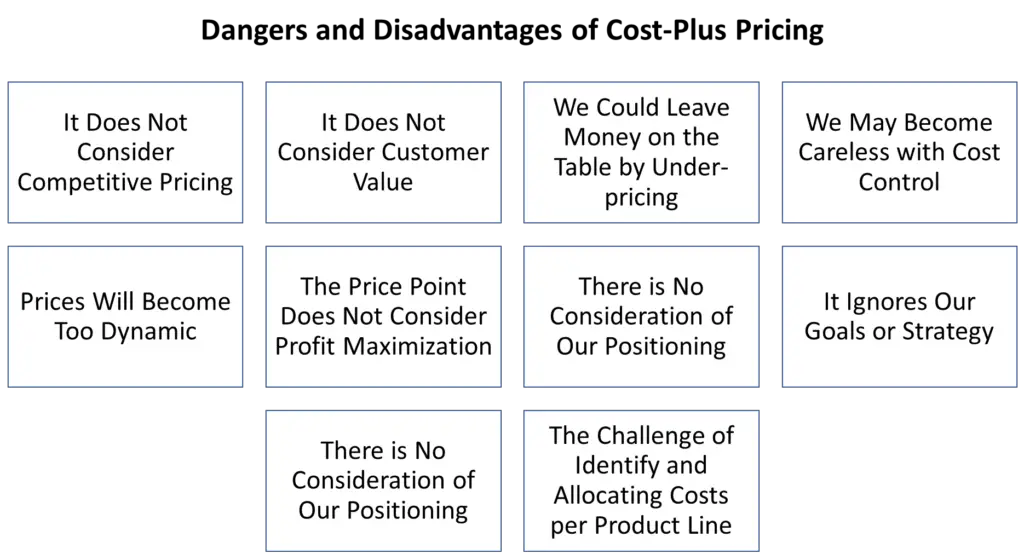

Here is a quick list of the disadvantages and limitations of cost-plus pricing, and each one will be discussed in more detail below.

- It Does Not Consider Competitive Pricing

- It Does Not Consider Customer Value

- We Could Leave Money on the Table by Under-pricing

- We May Become Careless with Cost Control

- Prices Will Become Too Dynamic

- The Price Point Does Not Consider Profit Maximization

- There is No Consideration of Our Positioning

- It Ignores Our Goals or Strategy

- There is No Consideration of Our Positioning

- The Challenge of Identify and Allocating Costs per Product Line

It Does Not Consider Competitive Pricing

Because cost-plus pricing only considers INTERNAL factors, many of which are unique to the business, it does not take into account the necessary external factors for setting retail prices.

In many industries, one of the most important consideration is pricing relative to competitors. Often our relative competitive price is based upon our brand strength, the channels we use, the quality of our products, and the preference and loyalty of our customer base.

However, cost-plus pricing ignores all of these important factors, and is based upon our internal cost structure only. It is likely that internal costs will vary between businesses.

For example, Walmart, with its enormous buying power and fined tuned and very efficient logistics system, would have a lower price point for variable costs than its competitors. This means that they can buy cans of soup and had them in a store at a much cheaper level than its competitors could buying the exact same soup product.

Plus, some businesses are very cost efficient and chase operational efficiencies, whereas others are less cost focus and have a higher cost infrastructure as a result.

Therefore, when we utilize a cost-plus pricing approach, we are simply marking up the cost of products to us – which will even make us very competitive in the marketplace (if we have a cost leadership advantage) or make us quite uncompetitive if we have excessive costs in our business operations.

In many product categories, especially for supermarket-style products or for products where people shop around on price, we CANNOT ignore competitive pricing – which would be a negative outcome of only relying upon a cost-plus pricing method.

It Does Not Consider Customer Value

Again, because cost-plus pricing is based upon INTERNAL factors only, we have a price point decided by the business itself (and its overall level of cost efficiency and buying power) with no consideration of external factors.

One of the most critical external factors is customer value. As we know, customer value is the set of benefits that a consumer perceives that they get from a product less the cost of acquiring the product.

Therefore, if we use cost-plus pricing, we may end up pricing the product at such a high level that consumers do NOT perceive value at that price – and therefore would not buy the product.

It is critical when pricing most products that we consider the price points that consumers perceive they received good value. This does not mean that we need to price low, but price appropriately for the set of product benefits received by the consumer and consistent with our competitive position.

We Could Leave Money on the Table by Under-Pricing

This cost-plus pricing limitation is connected to the above point, where we are not considering customer value. And the phrase, “leave money on the table” is slang for short-changing ourselves or limiting the profit that we could make, based upon the value of our product to consumers.

If we have a very efficient cost structure, then using cost-plus pricing may mean that we set quite low retail prices, especially as compared to what consumers are willing to pay.

In some cases, this may be a suitable strategy if cost and price leadership is our core strategy – but in most cases it would lead to limiting our profitability.

For example, we may be able to produce a product for $20, which we markup to $30 retail price. But if many consumers were willing to pay $50 for that product, then we are leaving $20 on the table after each purchase. In other words, we could increase our profit margin by $20 per sale.

By ignoring perceived customer value – and what price consumers are willing to pay for our product and set of benefits – we are potentially risking substantial profits.

We May Become Careless with Cost Control

For a business that is relied upon cost-plus pricing as their prime price setting mechanism, then the cost structure no longer matters to the firm. Why? This because they simply markup the cost by percentage, with no consideration of competitive position or consumer value.

In this case, it no longer matters what they costs are – because they believe that they can recoup them through higher prices in in all cases.

For example, a business that would normally produce a product for $20, and then becomes careless with their cost structure (of takes on additional expenses) – and that same product is now $40 – that simply doesn’t matter.

Instead of the business selling the product at a retail price of $50, like before, they would increase their price to $70 or more. As you can see, in their calculation they maintain a $30 profit market.

In reality, we understand supply and demand and would know that unit sales are most likely to fall if we increase the retail price by $20 – but to a company reliant upon cost-plus pricing and doing this on a spreadsheet – it doesn’t appear to make any difference.

As a result, the corporate culture of the company in this case would not be concerned with cost and operational efficiency. While that may be appropriate for very strong brands or unique product offerings, in most cases this will result in a bad business outcome, by reducing unit sales and market share.

Prices Will Become Too Dynamic

Costs constantly change for any business. Supply costs alter, staff numbers and wages will increase/decrease over time, marketing spends go up and down, logistics and transport costs vary, the price of oil/gas/electricity changes regularly, communication costs – there’s no end to it.

If we are using costs as the basis of setting prices – then this means that our prices will consistently change. Perhaps in some industries this is expected and common – such as pricing airline tickets and perishable food – in other industries it is a big concern.

Let’s assume that we have a local coffee shop. If we adjusted prices each time our cost change – then we would be changing the price of our coffee almost daily. For example, our electricity bill goes up by $100 per week – and that means we will have to increase the price of coffee from $5.00 to $5.20. And then next week, we replace a senior employee with a junior employee (lowering our salary costs, which then means we can then reduce the cup of coffee to now $4.87.

As you can see, this would cause customer frustration and dissatisfaction, as we have frequent price fluctuations. Best to be avoided!

The Price Point Does Not Consider Profit Maximization

The vast majority of businesses are focused upon maximizing long-term profitability. Using a cost-plus pricing method will not maximize profits as it does not consider elements of supply and demand, customer value, and competitive position.

Instead, we are simply allocating a percentage margin (markup) to our internal cost structure. While that is one consideration of pricing – making sure that we cover costs adequately – it is a very ineffective tool for setting prices to ensure profits are maximized.

There is an alternative approach to price setting, known as marginal pricing, which is more effective in this regard.

As outlined above, without taking into account customer value, we are unclear about the price points that consumers are willing to pay. In addition, we are not taking into account our relative competitive price, nor are we considering our brand strength and set of product benefits.

And we are also ignoring the demand curve for our product, which can essentially take into account the above factors. For example, how many units will we sell if we price at $10 versus how many units will be sell if the price at $12?

We can assume that we are likely to sell less units at $12, but we are adding $2 to our profit margin – which is substantial for a product price that only $12. Therefore, we need to run pricing scenarios, and perhaps test prices in the marketplace, to work out what price point delivers maximum profits.

This does not mean that we should look to rip customers off but provide true value and ensure that customers continue to buy from us – which will maximize long-term profitability – which is our prime goal in most cases.

Reliance upon cost-plus pricing independently all other pricing mechanisms, is unlikely to help us maximize profitability.

There is No Consideration of Our Positioning

Price is a core marketing mix element that you find in the 4P’s/7P’s of marketing. This means that is a marketing tool, not just a financial component of profitability.

In most product categories, prices are cues used by consumers to interpret the quality and positioning of a brand or product. Generally higher price points generally communicate higher quality and a superior brand.

If we have worked to build a strong brand, which has tangible and intangible benefits to the consumer, then we need to price the product accordingly to reflect our brand strength and superior offering.

By using a cost-plus pricing method, we are pricing our products completely independently of any marketing considerations. In this case, it is possible that we underprice our products – which would have the impact of damaging our brand reputation.

Price is the mark/symbol of quality that we set on our own products and brands. Cost-plus pricing has the danger of setting that consumer cue too high or too low – that is inconsistent with our brand and positioning goals.

It Ignores Our Goals and Strategy

Every professional business sets goals and will have a strategy that they are looking to execute. Cost-plus pricing ignores these goals and strategy and operates independently.

For example, if our goal for the coming year is to increase our market share from 5% to 10%, then the likelihood is that we need to adopt a low relative competitive price. Or, an alternative approach would be to invest in brand building and adopt a high competitive price to indicate a superior product.

In both of these cases we are setting prices based upon what we are trying to achieve in the marketplace = our goals and strategy.

Setting prices based upon internal cost factors, without consideration of what we are trying to achieve, will undermine our market success and reduce the likelihood that we will deliver on our goals and successfully implement our strategy.

The Challenge of Identify and Allocating Costs per Product Line

In essence, the concept is quite simple – identify the various costs associated with producing and supplying each product or product line to the end consumer.

However, this can be quite challenging, especially for a larger and more complex business. If we have a relatively simple business, such as a small independent convenience store, then we may be able to complete this task with a good degree of accuracy.

But for a large complex business, this cost allocation task is quite challenging. As an example, let’s use a medium level business in terms of cost complexity – McDonald’s.

So what are the costs involved in producing a Big Mac? Obviously, we have the ingredients of the Big Mac itself, plus the packaging costs. And we would know these costs from the payments that we make to suppliers. So far so good – we should be out to work out the variable cost of the product quite easily.

However, now we turn to the more complex task of identifying and allocating the other costs – fixed and semi-variable costs associated with the Big Mac product. Some of these would include:

- Staff costs – both kitchen and serving staff, and in-store management staff

- Rental costs of the premises

- Depreciation and repairs costs

- Store cleaning costs and security costs

- Insurance, banking fees

- Electricity, cooking equipment, oils, flavorings, etc.

- Any franchise fees payable or an allocation of head office fixed costs

- Advertising/promotion costs per store (sometimes part of the franchise fees)

- Staff recruitment and training costs

- And many more…

Why are these costs included?

All the above costs are incurred as part of the overall business operation, which is necessary to produce and supply Big Macs and other products to McDonald’s customers. If we did not incur the above costs, then the business would not be able to function on an ongoing basis.

Therefore, each of these other cost components need to be allocated to a product or product line in order to generate a full understanding of the cost of a Big Mac and all other products.

And once we have identified all these costs that contribute to the production and supply of the various products in a McDonald’s store, we then have to allocated per product.

Why cannot we allocate costs evenly across the products that we sell? This is not entirely accurate because each product takes a different amount of time to prepare, which means the amount of staff time will vary.

Serving a drink is relatively automated usually with a machine that can pour a Coke by itself and the staff member simply puts a lid on it and gets a straw. In this case the amount of staff time allocated to that product is potentially only 10-15 seconds.

This is contrasted with the production of a more complex hamburger – which requires cooking time, then preparation time, then packaging, and then serving. Obviously, the staff member is making more than one hamburger or other product at a time – but the necessity of allocating additional staff time and cost is clear.

As we can see, this cost allocation process is now getting a little bit more complex. If we have a total salary bill for a large McDonald’s store of $500,000 per year, then we need to break down how much staff time was allocated to each product – and this can be quite a challenging and time-consuming task.

Not only that, but we need to allocate management time, advertising and promotion costs, and even head office costs to each product line as well. Again, these are costs necessary to run a successful business – and the cost need to be recovered in the retail price, and the unit profit margin, of each product.

At this point, when allocating fixed costs, we have the challenge of what method we use to do that. Some businesses will allocate it on the proportion of sales or revenue – or some others will try to have that cost more reflective of where management spend their time, or which products were more heavily promoted during the year.

Related Articles

- Cost-Plus Pricing Formula with Examples

- More Cost-Plus Pricing Examples

- Prices, costs, margins and purchase quantity

- Price premium metric

- When to Use Cost-Plus Pricing

- Free Excel Template for Cost-Plus Pricing

External Information